Learning involves explanations, which forces you to compare things.

Posted Jan 24, 2019

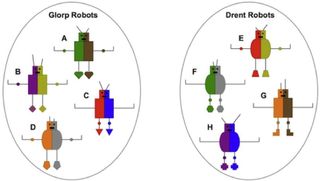

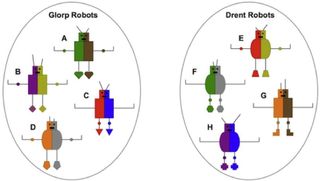

Figure 1 from Williams & Lombrozo

Source: Wiley Publishers

There are many reasons why we give explanations for things. Understanding how the world works is critical for being able to solve new problems. You often need good reasons when you make decisions.

Explanations can also help you learn subtle distinctions in the world. Joseph Williams and Tania Lombrozo studied this effect of explanation in a 2010 paper in the journal Cognitive Science. They had participants learn the rules for categorizing robots like the one in the figure. Some of the potential rules apply to most, but not all of the robots. For example, the Glorps tend to have square bodies, and the Drents tend to have round bodies, but there are exceptions. There are also less obvious rules that categorize perfectly. The Glorps have feet with angles on the bottom, while the Drents have feet that are flat on the bottom. People asked to explain why the robots were in a particular category were more likely than people who just studied the items to find rules that applied to all of the robots in a category.

Why does explanation help?

An interesting paper in the April 2019 issue of Cognition by Brian Edwards, Joseph Williams, Dedre Gentner, and Tania Lombrozo explored this question in more detail. Their studies suggest that explanation forces people to compare the items, which then leads to the discovery of the rules that apply to all of the category members.

Explanation requires comparisons, because in order to answer the “why” question, you need to find a rule that applies to all the members of one category, but not to the members of the other. That means that you have to compare all of the members within a category to find a quality that the category members share. You then have to compare members of one category to members of the other to see whether this potential rule reliably distinguishes members of one category from members of the other. By getting people to compare both within and between categories, explanation creates the conditions for finding the best rules.

Across several studies, participants were asked to examine pairs or groups of items that were sorted into categories. Participants who were prompted to explain why category members belonged to their respective categories were much more likely to find a rule that correctly classified all the category members than those in a control group, who were not given instructions to compare the category members. This replicates the previous finding I described. But participants who generated explanations also talked explicitly about comparing the options when describing what they did. Statistical analyses in the paper showed that people who stated that they compared the items were more likely to find a good classification rule than those who did not talk about comparing the items.

An interesting facet of these studies was that there were also several conditions across studies in which people were directly asked to compare items. Some of these instructions asked people to compare pairs of items. Some asked people to compare within a group. None of these instructions were as effective as asking people to generate explanations in getting people to find the best rule for classifying the robots.

A potential reason why comparison instructions are not that effective is that explanation gets people to do three things: It requires comparisons among the items within a category; it requires comparisons among items from different categories; and it also requires generating and testing hypotheses for classification that emerge from these comparisons. Explanation promotes comparison, but it goes beyond merely comparing the items.

This work fits with studies by Micki Chi and Kurt van Lehn that demonstrate that the best learners are the ones who explain things to themselves. Many times, you learn by reading something (like this blog post), watching a lecture, or having a conversation. These modes don’t necessarily require you to explain what you were just exposed to back to yourself. But, if you do generate an explanation, you’re much more likely to understand and remember the information later.

So, get in the habit of generating explanations whenever you have to learn something. It improves learning in a number of ways, including by making use of your powerful ability to make comparisons.

Posted Jan 24, 2019

Figure 1 from Williams & Lombrozo

Source: Wiley Publishers

There are many reasons why we give explanations for things. Understanding how the world works is critical for being able to solve new problems. You often need good reasons when you make decisions.

Explanations can also help you learn subtle distinctions in the world. Joseph Williams and Tania Lombrozo studied this effect of explanation in a 2010 paper in the journal Cognitive Science. They had participants learn the rules for categorizing robots like the one in the figure. Some of the potential rules apply to most, but not all of the robots. For example, the Glorps tend to have square bodies, and the Drents tend to have round bodies, but there are exceptions. There are also less obvious rules that categorize perfectly. The Glorps have feet with angles on the bottom, while the Drents have feet that are flat on the bottom. People asked to explain why the robots were in a particular category were more likely than people who just studied the items to find rules that applied to all of the robots in a category.

Why does explanation help?

An interesting paper in the April 2019 issue of Cognition by Brian Edwards, Joseph Williams, Dedre Gentner, and Tania Lombrozo explored this question in more detail. Their studies suggest that explanation forces people to compare the items, which then leads to the discovery of the rules that apply to all of the category members.

Explanation requires comparisons, because in order to answer the “why” question, you need to find a rule that applies to all the members of one category, but not to the members of the other. That means that you have to compare all of the members within a category to find a quality that the category members share. You then have to compare members of one category to members of the other to see whether this potential rule reliably distinguishes members of one category from members of the other. By getting people to compare both within and between categories, explanation creates the conditions for finding the best rules.

Across several studies, participants were asked to examine pairs or groups of items that were sorted into categories. Participants who were prompted to explain why category members belonged to their respective categories were much more likely to find a rule that correctly classified all the category members than those in a control group, who were not given instructions to compare the category members. This replicates the previous finding I described. But participants who generated explanations also talked explicitly about comparing the options when describing what they did. Statistical analyses in the paper showed that people who stated that they compared the items were more likely to find a good classification rule than those who did not talk about comparing the items.

An interesting facet of these studies was that there were also several conditions across studies in which people were directly asked to compare items. Some of these instructions asked people to compare pairs of items. Some asked people to compare within a group. None of these instructions were as effective as asking people to generate explanations in getting people to find the best rule for classifying the robots.

A potential reason why comparison instructions are not that effective is that explanation gets people to do three things: It requires comparisons among the items within a category; it requires comparisons among items from different categories; and it also requires generating and testing hypotheses for classification that emerge from these comparisons. Explanation promotes comparison, but it goes beyond merely comparing the items.

This work fits with studies by Micki Chi and Kurt van Lehn that demonstrate that the best learners are the ones who explain things to themselves. Many times, you learn by reading something (like this blog post), watching a lecture, or having a conversation. These modes don’t necessarily require you to explain what you were just exposed to back to yourself. But, if you do generate an explanation, you’re much more likely to understand and remember the information later.

So, get in the habit of generating explanations whenever you have to learn something. It improves learning in a number of ways, including by making use of your powerful ability to make comparisons.

[https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/ulterior-motives/201901/comparison-is-crucial-explanation]

No comments:

Post a Comment